Today’s episode is a conversation with AWAL CEO Lonny Olinick. We met in Culver City and had a wide-ranging conversation about how the business is doing, why artist development matters, deal terms, and why its approach is still unique in a landscape with more options than ever.

You can listen to our conversation here or read below for a highlight on one of the topics we discussed: artist development.

"I look at AWAL as the best artist development in the business." That quote from AWAL CEO Lonny Olinick sticks out as a contrast to the industry trend.

For many music companies, artist development is a practice in decline. Artists have more options than ever to build their careers, which raises the bar for what they are expected to achieve before partnering with record labels. I've often heard some version of "The label can take you from 60 to 100, but you have to get to 60." The “60” is normally some mixture of realized talent, monthly streaming listeners, social media following, and fan engagement.

When traditional labels sign artists who are not yet at that level, they push to own more of the artists' rights to justify their early bets. That’s how the underwriting works. AWAL also has different levels for artists as well, but even its earliest stage tier is still a selective process that gives artists long-term ownership of their music, along with the time and resources to build their careers. They may not offer the best deal in terms of pure dollar amount, but their goal is to offer the best value deal, as Lonny mentioned in our episode.

This shift mirrors what I've seen across industries. In venture capital, the rise of AI tools has similarly increased the bar for what companies are expected to achieve before they raise capital. AI enables individual founders to automate processes that once required entire teams. The concept of a 1-person company generating $1 billion in annual recurring revenue has become a legitimate target.

But this approach, in both music and venture, has its drawbacks. We may overlook talented artists or companies with the potential to get to 100 but get stuck at 40. Plus, if the DIY playbook of “getting to 60” becomes too standardized, it may diminish the uniqueness that artists have. The uniqueness that comes from personalized development. Rising artists try to emulate Taylor Swift, Drake, and others because there’s a proven model. They’re a lot like the founders who lean towards building B2B vertical SaaS startups because there’s a track record of venture-level outcomes.

A belief that some have in both industries is that raising the bar improves the odds for success, despite the talent that gets left behind as a result. But not every company in these industries needs to take that approach to success.

AWAL’s model works because artists aren’t uniform. They have a wide range of needs and services. That’s why multiple companies can succeed across the label and distribution landscape. AWAL has rising stars like Laufey who built significant streaming momentum independently, and established acts like Freddie Gibbs who wanted creative freedom without sacrificing industry support. AWAL offers them the flexibility they need while leveraging Sony's resources to compete at any level. Even if an artist eventually moves to a major label, AWAL benefits from the increased value of their catalog contributions.

In our conversation, Lonny and I also discussed Sony's impact on AWAL, why the lines between record labels and distributors continue to blur, and yes, we discussed the correct way to pronounce Laufey.

Listen to the full episode wherever you get podcasts!

Listen here: Spotify | Apple Podcasts | Overcast

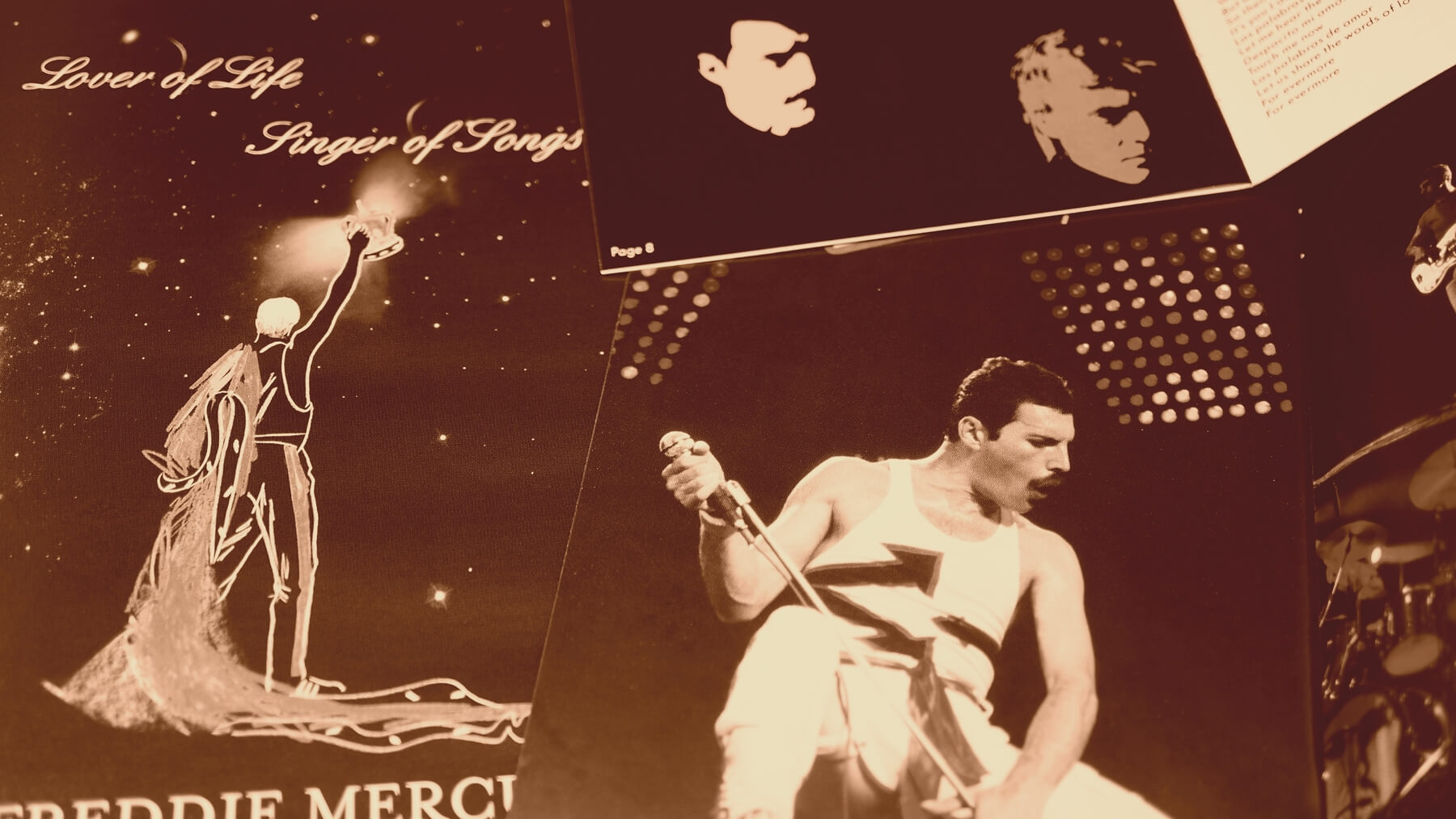

Chartmetric Stat of the Week - Freddie Gibbs

In our episode, I talked about how Freddie Gibbs still succeeds financially despite not having a lot of the same metrics. He has less than 4 million Spotify monthly listeners, gets around 85 radio spins daily, but still generates millions in revenue off of music that he largely owns himself.

.avif)